A chance meeting of a young woman in Derry in 1883 with an American led her to a central role as an eye-witness in a high profile 19th century murder story which culminated with a hanging in London.

A chance meeting of a young woman in Derry in 1883 with an American led her to a central role as an eye-witness in a high profile 19th century murder story which culminated with a hanging in London.

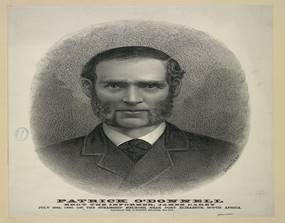

When Susan Gallagher (18), from Stranabrooey, Gweedore met Patrick O’Donnell (45), from Meenaclady it was the beginning of a journey which brought her from Derry to South Africa and changed the course of her life forever.

Newly discovered evidence from an archive file closed to public scrutiny for over 100 years suggests that O’Donnell who was hanged for the murder of the infamous informer James Carey on board a steamship off the Coast of South Africa may have been the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

Susan Gallagher was by his side on board the S.S. Melrose when he shot the former Invincibles leader who had a central role in the Phoenix Park murders of 1882 but who turned informer in order to avoid conviction and gave evidence against his colleagues, five of whom were hanged in 1883.

Since the shipboard killing happened on a British-registered vessel in international waters as Carey secretly attempted to flee into exile the authorities were permitted to extradite O’Donnell to London to be tried in the Old Bailey.

Susan Gallagher was quoted by a number of eye-witnesses who gave evidence in court as saying ‘No matter, O’Donnell, you’re no informer’ as she threw her arm around O’Donnell’s neck after the killing.

The previously unseen evidence from a British Home Office file suggests that an Old Bailey judge, Mr Justice Denman who heard the case against Patrick O’Donnell withheld crucial information in court which indicated that the jury believed that the killing was ‘without malice aforethought’.

A killing ‘without malice’ would equate to manslaughter and would have been punishable then by a short prison sentence rather the mandatory sentence of hanging which arose in cases of murder ‘with malice aforethought’.

A newly published book ‘The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell’ and a TG4 drama-documentary of the same name, reveals for the first time evidence found by author Seán Ó Cuirreáin which suggests that Mr Justice Denman misled the court, including the defence and prosecution teams as well as the press, when he amended and misrepresented the wording of a direct question from the jury which showed they were inclined to believe the killing was ‘without malice’.

Mr Justice Denman told the court that the jury, as they deliberated on their verdict having heard all the evidence, had submitted a question to him in writing in which they had sought a definition of ‘malice aforethought’. His reply was widely reported by the media who attended the high-profile case.

However, the actual question posed by the jury which was not read to the court is included in a file on the O’Donnell case in the British National Archive which was ordered to be ‘Closed until 1985’ and it suggests that the jury had no problem in understanding the concept of ‘malice aforethought’ but rather sought to ascertain if they reached a verdict of ‘murder without malice aforethought’ would the judge accept this verdict.

“It is highly significant that the judge misrepresented the jury’s question, withheld it in court and replaced it with an unasked question of his own” says Seán Ó Cuirreáin.

“This was a critical deflection by him which left the defence team in the dark and paved the way to a guilty verdict.

“The suggestion that the jury sought the judge’s approval for a verdict that the killing was without malice and the distortion of their legitimate query was, in fact, a matter of life or death for O’Donnell,” he added.

Ó Cuirreáin noted as ‘significant’ that no reference was made to the jury’s question in the official transcript of the trial.

All of the newspaper reports on the trial refer only to the judge’s amended question as reporters were unaware of true nature of the jury’s query.

However, the handwritten note of the jury’s question in blue pencil was attached by Mr Justice Denman to 61 pages of meticulous notes made by him during the course of the two-day trial in a document which was subsequent ordered to be closed to public scrutiny until 1985.

An earlier question posed by the jury was read in full to the court by Mr Justice Denman and his response to it attracted criticism from the defence team who said it favoured the prosecution case and was biased against Mr O’Donnell.

This too was omitted from the official trial transcript.

Patrick O’Donnell, who was born in the Gweedore Gaeltacht but had spent much of his life in America where he had become accustomed to carrying a gun, admitted to shooting Carey in front of witnesses but he argued that the killing was in self-defence.

O’Donnell and Susan Gallagher, who was introduced to ship passengers and crew on the journey as Mrs O’Donnell, had unknowingly befriended Carey and his wife during a three-week sea voyage from London to Cape Town as the informer and his family attempted to flee into hiding in South Africa under an assumed name.

Carey was one of the most reviled and despised figures in Ireland at the time and his evidence against colleagues who were later hanged was seen as treachery.

It emerged later that when the couple met in Derry, O’Donnell proposed that he would pay her passage to Cape Town if she accompanied him and that they would marry en route in London.

She agreed to the arrangement but a priest in London refused to marry them as they were unknown to him.

They agreed to continue their journey and marry at the first opportunity in South Africa.

They left Derry by boat for Liverpool on the first leg of their journey to new life where O’Donnell hoped to make his fortune in the diamond mines in the Kimberley region.

A Derry Journal reporter who visited O’Donnell’s native Gweedore was the first to establish an important fact in the case: Patrick O’Donnell was already married to a woman from the neighbouring parish of Cloughaneely who was living in Philadelphia.

It later emerged that O’Donnell and his wife Maggie McNulty had been living separately as he sought work in various palace in Pennsylvania and neighbouring states.

An attempt at reconciliation between the couple had failed shortly before he left America with a view of going to South Africa to make his fortune in the diamond mines there.

The status of Patrick O’Donnell and Susan Gallagher’s relationship was important as evidence from a wife could not be heard by the court as husbands or wives were prohibited by law at that time from giving evidence when a spouse was charged with a crime.

Susan Gallagher was summoned by warrant by Patrick O’Donnell’s lawyers to be brought back from South Africa to London in the hope of giving evidence on his behalf.

When interviewed by his lawyers in London on her return they decided not to call her as a witness as they felt her evidence might do more harm than good to their case.

Patrick O’Donnell’s wife Maggie McNulty accompanied by her brother-in-law, Roger McGinley also travelled from the US to Britain in the hope that she might be allowed give evidence on his behalf.

The case against O’Donnell in the Old Bailey had already concluded with a guilty verdict delivered by the time she had crossed the Atlantic and she returned immediately to Philadelphia.

O’Donnell was lauded as a hero for killing the informer whose death was celebrated throughout Ireland and in the Irish-American communities where he had spent half his life.

O’Donnell was lauded as a hero for killing the informer whose death was celebrated throughout Ireland and in the Irish-American communities where he had spent half his life.

An ‘O’Donnell Defence Fund’ established in America accumulated $55,000 (c. €1.5 million now) to employ a high powered legal team to defend him. Since O’Donnell had been granted American citizenship during his years there, the US President pleaded that he not be hanged.

The iconic French writer Victor Hugo also took up his case and contacted Queen Victoria directly with an urgent request to spare his life.

Such appeals were rejected and O’Donnell was hanged at Newgate Prison on 17th December 1883.

His death secured his immediate status as a national hero at home and abroad and he was celebrated as an Irishman who had died for Ireland.

In the aftermath of trial Susan Gallagher went to America and resurfaced in New York in June 1885 when she sought to sue Patrick Ford, the publisher of The Irish World who had raised funds for the defence of Patrick O’Donnell.

She claimed that O’Donnell ‘desired’ her to have £500 (approximately $2,500 then) of the money that Mr Ford had raised for his defence, that she had lived with the Ford family but had received only a portion of what she believed was due to her.

Mr Ford asserted that O’Donnell ‘never named Susan Gallagher, nor did he ask that one penny be given her’. He said that ‘including the expenses’ he had given Susan Gallagher $500 ‘out of pure generosity’, although she was ‘not entitled to a penny’. $300 of the amount he had given her was ‘in solid cash’ he said.

Patrick Ford also revealed that Patrick O’Donnell had asked that ‘his wife in Philadelphia’ Maggie McNulty be given £200.

Mr Ford said he was ‘generous’ with Mrs O’ Donnell and gave her $1,500 dollars, ‘$500 more than he told us to give her’.

Two large Celtic crosses were erected to commemorate Patrick O’Donnell, one in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, the second in his native Gweedore, where a public event in his honour is still celebrated annually.

Two large Celtic crosses were erected to commemorate Patrick O’Donnell, one in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, the second in his native Gweedore, where a public event in his honour is still celebrated annually.

The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell is published by Four Courts Press, price €17.95 (paperback) and available online from www.fourcourtspress.ie or from all good local booksellers.

The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell is also the title of the 90-minute feature-length drama-documentary commissioned from independent production house ROSG by TG4.

The drama-documentary has already secured international recognition with shortlisting at film festivals in Vancouver, Canada and Madrid, Spain and will have its first festival screening in Ireland at the Galway Film Fleadh (20th-25th July).

Tags: